Nora Ikstena is a world-renowned modern writer from Latvia. She was the center of attention at London Book Fair in 2018. Her famous book “Soviet Milk” (“Mother’s Milk” in its original language) is about Soviet past. The novel is dealing with disobedience and freedom, rejection and pain. It is a story about totalitarian and patriarchal system told by two women – mother and daughter. “Mother’s Milk” was published in Georgia last year (publishing house “Books in Batumi”, translator Mzia Koberidze).

The interview was done at the end of July 2019, in Latvia. It was mainly focused on rethinking the Soviet past, but the conversation touched many different topics.

- First of all, I would like to ask you about the “Soviet Milk”. Why did you write this novel?

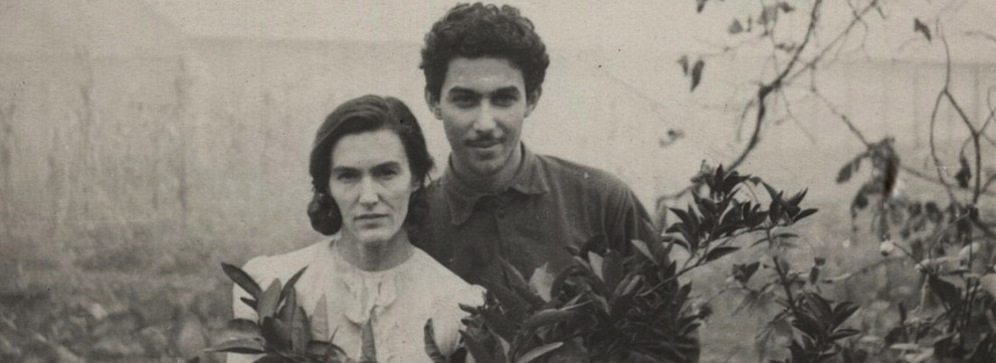

The story of this book starts in 1998, when my first novel “Celebration of Live” was published. It is translated in Georgian as well. At that time I was 28 years old. The story is about the woman, who goes to her mother’s funeral, even though she does not know her well. At the funeral she meets relatives and close friends of her mother, talks with them and learns about her mother’s life. The book was a big success in Latvia. It was translated in many languages, but the most significant fact was that I received the first copy of the book from publishing house on the day of my mother’s funeral. My mother was 54 when she died, she never read my novel and I believe I started thinking about “Soviet Milk” since her funeral. I had this novel in my mind for 25 years. During this period, I worked, traveled, wrote, studied but the topic of relationship between mother and daughter was always very important for me and I had a feeling that I should go back to it. In 2013 there was an idea to create series of novels about 20th century Latvia. 14 modern novelists came together. Each had to select a period from 20th century and work on it. I agreed to be part of it because I already knew what I was going to write. I selected 1969-1990 – the period between my birth and the fall of Berlin wall. The “Soviet Milk” was the first novel which I wrote here, in my own house. I was ready to work on it. It took one year to write the novel. Writing was pleasure and I had a feeling there were no boundaries for me in the Latvian language. Every theme and emotion of the past came to me vividly as I was writing. I choose a concise and simple language and told the story through two women – mother and daughter. I wanted to put these two voices in one story. I myself needed to write this book, in order to understand what happened with my mother, to understand relationships and the time in which she lived.

- New generation does not know much about Soviet past, in Georgia as well. Is it the same in Latvia?

Yes it is. And that is why many teachers of Latvian language and literature thanked me. They told me that pupils do not understand the past with just facts from history, they read “Soviet Milk” and then everything becomes clear. My niece, who is a musician and lives in London, composed music for my mother after reading the book. She was only three years old when her grandmother died, she did not even remember her well. With this book she learned the story of the family and become acquainted with her grandmother.

- What was the reaction of the Latvian readers?

I did not expect such a response. Many books were sold. During two and a half years I visited almost all libraries in Latvia, including village libraries and librarians were showing me long lists of the readers who took the book. In some libraries they even introduced one-day reading rule – they give you the book and you should return it in 24 hours in order to pass it to another reader.

- How was the novel received by western readers?

I was surprised by British readers. They are very snobbish, and are not interested in anything, including translated literature. But it was surprising how the readers want to fill the gaps of knowledge about the Soviet Union. My interviews on BBC and other channels where not only about the literature, but we talked a lot about political situation.

It has been four year since “Soviet Milk” was published; it has been translated in many languages. This novel begins new life in Italy, United States, England, Georgia, Sweden, Japan… I’m attending my novel’s presentations all over the world and you can’t imagine how little people know about what happened behind the Iron Curtain. What we went through - the Soviet Past, is totally unknown for them.

- I would like to ask you about the title of the novel. In Britain it was named “Soviet Milk”. Was the change of the title acceptable to you?

When my British publisher told me that we had to change the title, I was angry, but I did not know what the new title should be. They explained that they wanted British readers to remember the book and for this an impressive title was important. And then, half-angry, half-joking I suggested to name it “Soviet Milk”, that made them very excited. They even asked book dealers and reviewers for advice about the title and got all positive responses on “Soviet Milk”. I did not think that it would be such a serious issue, but it is, as it appears! So, I sacrificed the Latvian title of the book so that Latvian literature can be read in Britain.

- Let’s move to the memory of political issues. In your opinion, how does Latvia, at a society level, cope with the Soviet Past?

In Latvia this process started at the end of 1990's. People’s first reaction was to avoid the past, not to remember it. We were starting a new life, we would be a part of the EU and NATO, travel to resorts, buy new houses and cars, etc. But then, at some point, my generation realized that the past trauma always follows us, it is always with us and it is impossible to get rid of it with only silence. It is impossible not to talk about it, even in the literature. The series of novels on Soviet past worked very well as psychotherapy and helped to analyze what was reality, how we lived in the cages. The brother of my grandmother emigrated to London and they never saw each other. My grandmother could not even go to his funeral. These are small family details, but with such small facts the big pictures of history is drawn. Behind the historical facts there are individual’s life, people’s lives, their painful stories. I think with this series of publication Latvian people started to remember what happened: how we lived, are we really free, what was good and what was bad at that time… that period somehow brought people closer to each other, this was a different type of communication…

- You know Georgia well. What do you think is our attitude towards Soviet Past?

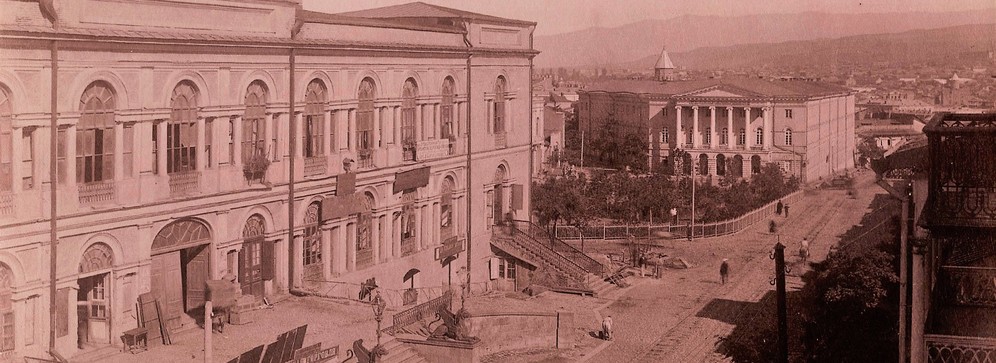

For 11 year I lived between Georgia and Latvia. My ex-husband is Georgian. I believe, Georgians look at the past more easily. I think, during the Soviet period you had a different situation. In some ways you were very friendly with Russia. You were diplomats. You knew how to use this regime, how to deal with it. For us, Latvians, this was really two totally different universes. Sitting in the kitchen we cursed communists and then we went into the streets. I think we were lucky to catch the last train into the EU. One other big difference between us is that in Latvia we never had a split society; we did now have a civil war. There is nothing more horrifying than a civil war. I first came to Georgia in 2008, after Russian-Georgian war. We were strongly supporting you from Latvia. Since then, for 11 years Georgia became my second homeland. I even was baptized as an Orthodox there. I lived even with nuns in Bodbe Monastery.

- I want to ask you about the literature of small countries. I think, that besides the cultural value, there as a political implication for small countries to learn about each others literature. However, there are many barriers on the way, including translation problems, small markets….What do you think, how small countries should act in the literature world dominated by big countries and markets?

The processes are now changing. The world of literature – European, American, British are interested in literature of small countries, they find many interesting things there. Besides, we have very good translators in Latvia. We are working on this for last 15 years. What I learned from my success and generally, from the success of Latvian literature is that if you want to be famous writer abroad, at first, you should be recognized in your country. For your reader, you should be a writer in your mother tongue. The Latvian language is my home.

- And finally, I would like to ask the most important thing. Do you think that after collapse of USSR we got the freedom that the mother from your novel was seeking?

I might not like many things in EU, but now we have the freedom of thought, travel, education, freedom to learn languages, rent a flat. This is freedom without borders. Living in the cage means being imprisoned; that means you cannot go anywhere, or learn languages, you will not have other experiences; but how free you are it again depends on you. Even in free society it is possible to be imprisoned in a cage. Having no borders means victory and we should value it. In Soviet Union we were hamsters in cages, now we have a possibility to be free.